Coffee was first produced commercially in El Salvador in the 1850s. It soon became a favoured crop, with tax breaks for producers. Coffee production became an important part of the economy and the country’s main export, and by 1880 El Salvador was the fourth-largest producer of coffee in the world, producing more than twice as much as it does today.

The growth of the coffee industry came about in part because El Salvador was moving away from its previous dominant crop, indigo, after the invention of chemical dyes in the mid-19th century. The land used to grow indigo had been controlled by a relatively small landed elite. Coffee production required a different type of land, so these landed families used their influence in government to pass laws to push the poor from their land so that it could be absorbed into the new coffee plantations. Compensation to those indigenous people was all but nonexistent, sometimes they were simply offered the chance to work seasonally on the newly established coffee plantations.

By the early 20th century, El Salvador would become one of the most progressive of the Central American nations, the first with paved highways and investment in ports, railroads and lavish public buildings. Coffee helped fund infrastructure and integrate indigenous communities into the national economy, but it also served as a mechanism for the landed elite to maintain political and economic control over the country.

The aristocracy of the time exerted their power through the support of military rule from the 1930s, and this became a period of relative stability. The growth of the coffee industry in the decades that followed helped support the development of a cotton industry and light manufacturing. Up until the civil war of the 1980s, El Salvador had a reputation for quality and efficiency in its coffee production, with well-established relationships with importing countries. The civil war, however, would have a dramatic impact on this, as production fell and foreign markets looked elsewhere for their coffee.

El Salvador’s unusually high percentage of heirloom coffee varieties and agriculturally rich farmland mean exports for its sweet flavoured coffees have increasing potential.

El Salvador’s unusually high percentage of heirloom coffee varieties and agriculturally rich farmland mean exports for its sweet flavoured coffees have increasing potential.

HEIRLOOM VARIETIES

Despite the drop in production and exports, the civil war had an unexpected benefit for the coffee industry. Throughout much of Central America at the time, coffee producers were replacing their heirloom varieties with newly developed high-yield varieties. The cup quality of these new varieties did not match that of the heirloom varieties, but yield was favoured over quality. El Salvador, however, never went through this process. The country still has an unusually high percentage of heirloom Bourbon trees, in total producing about 68 per cent of its coffee. Combined with its well-drained, but mineral-rich volcanic soils, the country has the potential to produce some stunningly sweet coffees.

THE PACAS VARIETY

In 1949 a mutation of the Bourbon variety was discovered by Don Alberto Pacas on one of his farms. It was named after him, and was later crossed with Maragogype, a variety of coffee with very large beans, to create the Pacamara variety. Both desirable varieties remain in production in the region and in neighbouring countries. For more information on varieties, see Coffee Varieties.

This has been the focus of much of El Salvador’s recent coffee marketing and it has worked hard to regain its standing among the coffee-producing countries and re-establish old relationships with consuming nations. Large estates still exist in El Salvador, but there are also a lot of small farms. It is a great country to explore, as there are many stunning coffees, full of sweetness and complexity.

In a sea of ripe coffee cherries at El Paste near Santa Ana, this worker shovels the harvest ready for processing. The Apaneca-Ilamatpec region is the biggest producer of coffee in El Salvador.

In a sea of ripe coffee cherries at El Paste near Santa Ana, this worker shovels the harvest ready for processing. The Apaneca-Ilamatpec region is the biggest producer of coffee in El Salvador.

TRACEABILITY

The infrastructure in place means that it is relatively easy to retain the traceability on high-quality coffees right back to farm level, and many farms are able to create micro-lots based around process and variety.

ALTITUDE CLASSIFICATIONS

El Salvador still sometimes classifies coffee based on the altitude at which it was grown. These classifications have no relation to either quality or traceability.

Strictly High Grown (SHG): grown above 1,200m (3,900ft)

High Grown (HG): grown above 900m (3,000ft)

Central Standard: grown above 600m (2,000ft)

Although volcanic activity can threaten production, plantations in the Apaneca-Ilamatepec region consistently grow competition-winning coffee due to the excellent soil.

Although volcanic activity can threaten production, plantations in the Apaneca-Ilamatepec region consistently grow competition-winning coffee due to the excellent soil.

TASTE PROFILE

The Bourbon variety coffees from El Salvador are famously sweet and well balanced, with a pleasing soft acidity to give balance in the cup.

GROWING REGIONS

Population: 6,377,000

Number of 60kg (132lb) bags in 2016: 623,000

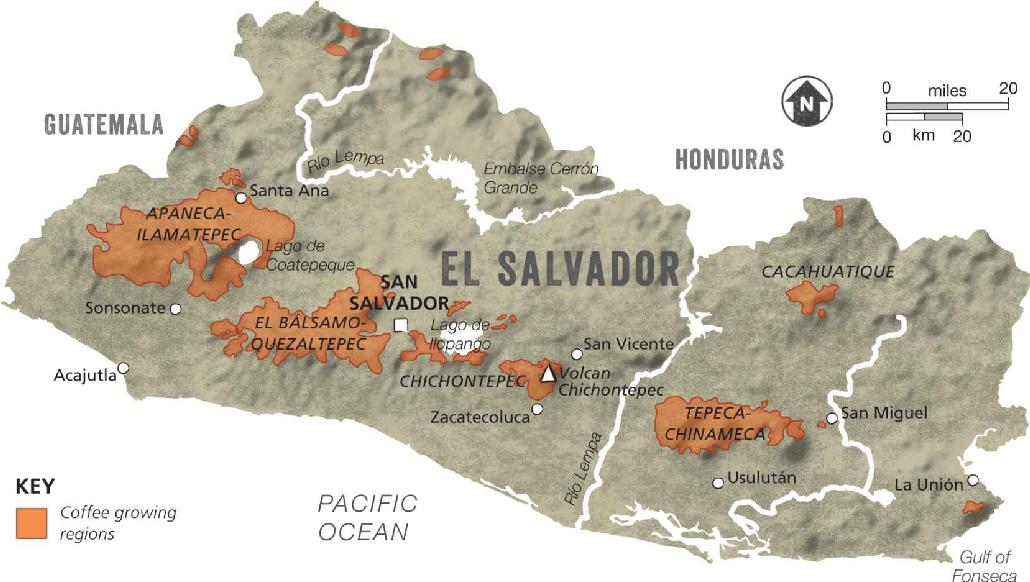

Most coffee roasters do not use the region names when describing coffees. While they are distinct, well-defined regions, some would argue that El Salvador itself is so small that it could be classified as a single region, with clearly defined pockets of coffee growing within it.

APANECA-ILAMATEPEC MOUNTAIN RANGE

With a reputation for great quality, this area produces many competition-winning coffees, despite the volcanic activity here. The Santa Ana volcano erupted as recently as 2005, having a massive impact on production for a couple of years. This is the largest-producing region of the country and it was probably here that coffee was first cultivated in El Salvador.

| Altitude: | 500–2,300m (1,600–7,500ft) |

| Harvest: | October–March |

| Varieties: | 64% Bourbon, 26% Pacas, 10% others |

ALOTEPEC-METAPAN MOUNTAIN RANGE

This mountain range is one of the wetter regions of El Salvador, with over one-third more rainfall than average. The region borders both Guatemala and Honduras, yet despite its proximity to those countries the coffees here remain distinct and different.

| Altitude: | 1,000–2,000m (3,300–6,600ft) |

| Harvest: | October–March |

| Varieties: | 30% Bourbon, 50% Pacas, 15% Pacamara, 5% others |

EL BÁLSAMO-QUEZALTEPEC MOUNTAIN RANGE

Some of the coffee farms in this region overlook the capital city of San Salvador, from high up on the sides of the Quetzaltepec volcano. This region was home to the pre-Hispanic Quetzalcotitán civilization, who worshipped the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoat, still a common symbol in Salvadorian culture today. The mountain range also takes its name from the Peruvian Balsam produced there, an aromatic resin used in perfumes, cosmetics and medicines.

| Altitude: | 500–1,950m (1,600–6,400ft) |

| Harvest: | October–March |

| Varieties: | 52% Bourbon, 22% Bourbon, 26% mixed & others |

CHICHONTEPEC VOLCANO

Coffee was late coming to this region in the centre of the country, with barely fifty bags of coffee being produced here in 1880. However, the volcanic land is extremely fertile, and today the area is home to many coffee farms. The traditional practice of planting alternating rows of coffee and orange trees for shade is still common: some believe this imparts an orange blossom quality to the coffee, though others attribute this soft citrus element to the Bourbon variety that is grown here.

| Altitude: | 500–1,000m (1,600–3,300ft) |

| Harvest: | October–February |

| Varieties: | 71% Bourbon, 8% Pacas, 21% mixed & others |

TEPECA-CHINAMECA MOUNTAIN RANGE

This region is the third-largest producer of coffee in the country. Here they serve coffee with corn tortillas called tustacas, made with salt and dusted with sugar or made with a little panela (cane sugar).

| Altitude: | 500–2,150m (1,600–7,100ft) |

| Harvest: | October–March |

| Varieties: | 70% Bourbon, 22% Pacas, 8% mixed & others |

CACAHUATIQUE MOUNTAIN RANGE

Captain General Gerardo Barrios was the first Salvadorian president who saw the potential economic value of coffee and it is rumoured that he was one of the first to cultivate coffee in El Salvador, on his property in this region, close to Villa de Cacahuatique, now called Ciudad Barrios. This mountain range is known for its abundance of clay, used to make pots, platters and decorative items. Farmers here often have to dig large holes in the clay-like earth and fill them with rich soil, in which to plant their young trees.

| Altitude: | 500–1,650m (1,600–5,400ft) |

| Harvest: | October–March |

| Varieties: | 65% Bourbon, 20% Pacas, 15% mixed & others |

The powdery remains of coffee shells at La Majada estate in El Salvador are recylced for use as compost. Minerals and trace elements in the waste help nourish soil for the plants.

The powdery remains of coffee shells at La Majada estate in El Salvador are recylced for use as compost. Minerals and trace elements in the waste help nourish soil for the plants.

Washing coffee beans at Finca Vista Hermosa Coffee Plantation, Agua Dulce, Guatemala.

Washing coffee beans at Finca Vista Hermosa Coffee Plantation, Agua Dulce, Guatemala.