Despite the fact that neighbouring Ethiopia is considered the home of coffee, Kenya did not start production until relatively late. The earliest documented import of coffee dates to 1893 when French missionaries brought coffee trees from Réunion. Most agree that the variety of coffee they brought was Bourbon. It yielded its first crop in 1896.

Initially coffee was produced on large estates under British colonial rule, and the resulting crop was sold in London. In 1933 the Coffee Act was passed, establishing a Kenyan Coffee Board and moving the sale of coffee back to Kenya. In 1934 the auction system was established and it is still in use today; a year later protocols were created for the grading of coffee to help improve quality.

Not long after the Mau Mau uprising in the early 1950s, an agricultural act was passed to create family holdings that combined subsistence farming with the production of cash crops for additional income. This act was known as the Swynnerton Plan, named after an official in the Department of Agriculture. This marked the start of the transfer of coffee production from the British to the Kenyans. The effect on the production of smallholdings was significant, with total income rising from £5.2 million in 1955 to £14 million in 1964. Notably, coffee production accounted for 55 per cent of this increase.

Kenya gained independence in 1963, and now consistently produces extremely high-quality coffees from a variety of sources. The research and development in Kenya is considered excellent, and many farmers are highly educated in coffee production. The Kenyan auction system should help to reward quality-focused producers with better prices, but while buyers are paying high prices for the excellent coffees, corruption within the system may prevent those premiums filtering back to the farmers.

Kenyan women carry buckets of freshly picked ripe coffee cherries to be sorted and processed.

Kenyan women carry buckets of freshly picked ripe coffee cherries to be sorted and processed.

GRADING

Kenya uses a grading system for all of its exported coffee, regardless of whether the lot is traceable or not. As in many other countries, the grading system uses a combination of bean size and quality. The definitions clearly define size and, to some extent, they also assume quality is linked to the size of the beans. While this is often true – the AA lots often being the superior coffees – I have recently seen harvests where the AB lots appeared to be more complex and of higher quality than many of the AA lots.

E – These are the elephant beans, the very largest size, so lots tend to be relatively small.

AA – This is a more common grade for the larger screen sizes (see Sizing and Grading), above screen size 18, or 7.22mm. Typically, these fetch the highest prices.

AB – This grade is a combination of A (screen size 16, or 6.80mm) and B (screen size 15, or 6.20mm). This grade accounts for around thirty per cent of Kenya’s annual production.

PB – This is the grade for peaberries, where a single bean has grown inside the coffee cherry instead of the more usual two.

C – This is the grading size below the AB category. It is unusual to see this grade in a high-quality coffee.

TT – A smaller grade again, normally comprising the smaller beans removed from AA, AB and E grades. In density sorting, the lightest beans are usually TT grade.

T – The smallest grade, often made up of chips and broken pieces.

MH/ML – These initials stand for Mbuni Heavy and Mbuni Light. Mbuni is the name used for naturally processed coffees. These are considered low quality, often containing underripe or overripe beans, and they sell for a very low price. They account for around seven per cent of the annual production.

TRACEABILITY

Kenya’s coffee is grown both on large estates, and by smallholders who feed their coffee into their local washing station. This means it is possible to get extremely traceable coffees from the single estates, but in recent years the higher-quality coffees have increasingly come from the smallholders. Typically what one might find is a particular lot from a washing station that will still carry a size grading (such as AA), though that lot may have come from a group of several hundred farmers. These washing stations (or factories as they are known) play a role in the quality of the final product, so these coffees are definitely worth seeking out.

An aerial view of a coffee plantation in Kenya. The country consistently produces beans of a very high quality, from a variety of sources that include large estates and smallholders.

An aerial view of a coffee plantation in Kenya. The country consistently produces beans of a very high quality, from a variety of sources that include large estates and smallholders.

Women grade beans according to their size and quality at a coffee factory in Komothai, in Ruiri, Kenya.

Women grade beans according to their size and quality at a coffee factory in Komothai, in Ruiri, Kenya.

KENYAN VARIETIES

Two particular Kenyan varieties attract great interest from the speciality coffee industry. These are named SL-28 and SL-34, and are among the forty experimental varieties produced as part of the research led by Guy Gibson at Scott Laboratories. These make up the majority of high-quality coffee from Kenya, but they are susceptible to leaf rust.

A lot of work has been done to produce rust-resistant varieties in Kenya. Ruiru 11 was the first to be considered a success by the Kenyan Coffee Board, although it was not warmly received by speciality coffee buyers. More recently, they have released a variety called Batian. There remains some scepticism towards its cup quality after the disappointment of Ruiru, although quality seems to be improving and there is more positivity around the potential of Batian to have great cup quality in the future.

TASTE PROFILE

Kenyan coffees are renowned for their bright, complex berry/fruit qualities as well as their sweetness and intense acidity.

GROWING REGIONS

Population: 48,460,000

Number of 60kg (132lb) bags in 2016: 783,000

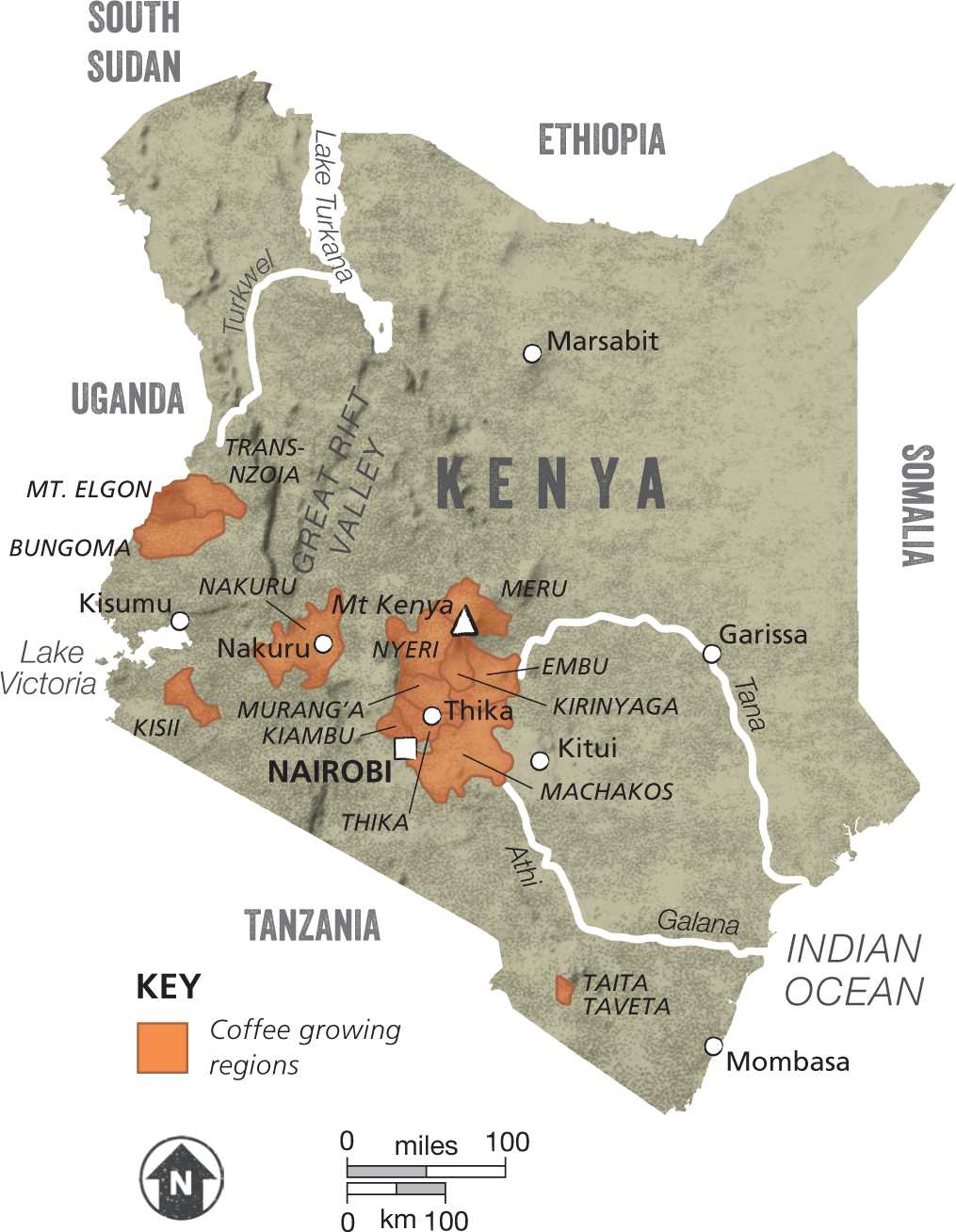

Central Kenya produces most of the nation’s coffee, and the best Kenyan coffees come from this part of the country. There is growing interest in the coffees being produced in Western Kenya, in the Kisii, Trans-Nzoia, Keiyo and Marakwet regions.

NYERI

The central region of Nyeri is home to the extinct volcano of Mount Kenya. The red soils here produce some of the best coffee in Kenya. Agriculture is hugely important to the area and coffee is one of the main crops. Cooperatives of smallholder producers are common, rather than large estates. The coffee trees in Nyeri produce two crops a year and the main crop tends to produce higher-quality lots.

| Altitude: | 1,200–2,300m (3,900–7,500ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian |

MURANG’A

Around 100,000 farmers produce coffee in the Murang’a region, within the Central Province. This inland region was one of the first to be settled by missionaries, who were prevented from settling around the coast by the Portuguese. This is another region that benefits from the volcanic soil, and also has more smallholders than estates.

| Altitude: | 1,350–1,950m (4,400–6,400ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian |

KIRINYAGA

The eastern neighbour of Nyeri, this county also benefits from volcanic soils. The coffee tends to be produced by smallholders and the washing stations have been producing some very high-quality lots that are well worth trying.

| Altitude: | 1,300–1,900m (4,300–6,200ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian |

EMBU

Near Mount Kenya, this region is named after the town of Embu. Approximately seventy per cent of the population are small-scale farmers, and the most popular cash crops are tea and coffee. Almost all of the coffee comes from smallholders and the region is a relatively small producer.

| Altitude: | 1,300–1,900m (4,300–6,200ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian, K7 |

MERU

Coffee is grown on the slopes of Mount Kenya and in the Nyambene Hills, mostly by smallholders. The name refers to both the region and the Meru people who inhabit it. In the 1930s, these people were among the first Kenyans to produce coffee, as a

result of the Devonshire White Paper of 1923, which asserted the importance of African interests in the country.

| Altitude: | 1,300–1,950m (4,300–6,400ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian, K7 |

KIAMBU

This central region’s production is dominated by large estates. However, the spread of urbanization has seen the number of estates decline as owners have found it more profitable to sell their land for development. Coffees from the region are often named for places within it, such as Thika, Ruiru and Limuru. Many of the estates are owned by multinational companies, which means that farming practices are often mechanized with an eye towards higher yields rather than quality. There are a reasonable number of smallholders in the region, too.

| Altitude: | 1,500–2,200m (4,900–7,200ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian |

MACHAKOS

This is a relatively small county in the centre of the country, named after the town of Machakos. Coffee production here is a mixture of estates and smallholders.

| Altitude: | 1,400–1,850m (4,600–6,050ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34 |

NAKURU

This region, in the centre of the country, has some of the highest-growing coffee in Kenya. However, some trees suffer from ‘dieback’ at high altitudes and stop producing. The region is named after the town of Nakuru. Coffee is produced by a mixture of estates and smallholders, although production is relatively low.

| Altitude: | 1,850–2,200m (6,050–7,200ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Ruiru 11, Batian |

KISII

This region is in the southwest of the country, not far from Lake Victoria. It is a relatively small region and most of the coffee comes from cooperatives of small producers.

| Altitude: | 1,450–1,800m (4,750–5,900ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | SL-28, SL-34, Blue Mountain, K7 |

TRANS-NZOIA, KEIYO & MARAKWET

This relatively small area of production in Western Kenya has seen some growth in recent years. The slopes of Mount Elgon provide some altitude, and most of the coffee comes from estates. Coffee is often planted to diversify farms that once focused on maize or dairy.

| Altitude: | 1,500–1,900m (4,900–6,200ft) |

| Harvest: | October–December (main crop), June–August (fly crop) |

| Varieties: | Ruiru 11, Batian, SL-28, SL-34 |