Coffee drinking is often tied into a ritual, a specific part of our day. We might drink a cup of coffee first thing in the morning, or as a break from work. Our attention is usually focused on the people we are with, or the newspaper we are reading over breakfast. Few people really concentrate on tasting the coffee they drink, but when they start to notice it, their appreciation increases rapidly.

The process of tasting happens in two different places – in our mouths and in our noses – and it is helpful to think about these two parts of the process separately when learning to taste and talk about a coffee. The first part of the process occurs on the tongue and it is here we detect the relatively basic tastes of acidity, sweetness, bitterness, saltiness and savouriness. When reading the description of a coffee, we might be attracted to the flavours described, such as chocolate, berries or caramel. These flavours are actually detected the same way as smells – not in the mouth but by the olfactory bulb in the nasal cavity.

For most people these two separate experiences are completely intertwined, and the separation of taste and smell is extremely difficult. It gets easier if you try to focus on one particular aspect at a time, rather than taking the extremely complex taste experience in one go.

PROFESSIONAL TASTERS

Before it reaches the final consumer, a coffee will have been tasted a number of different times along its journey through the coffee industry. Each time it is tasted, the taster might be looking for something different. It might first be tasted early on to detect any presence of defect. It will then be tasted by a roaster as part of the purchasing process, or by a jury ranking coffees for an auction of the best lots from a particular place. It will be tasted by the roaster again as part of their quality control to make sure that the roasting process was done correctly and then it may be tasted by a café owner selecting the range they wish to stock. Finally it will be tasted, and hopefully enjoyed, by the consumer.

The coffee industry uses a pretty standardized practice called ‘cupping’ to taste coffee. The idea behind cupping is to avoid any impact on flavour from the brewing process, and to treat all coffees being tasted as equally as possible. For that reason, a very simple brewing process is used, as bad brewing can easily change the flavour of a coffee quite dramatically.

A fixed amount of coffee is weighed for each bowl. It is ground at a fixed setting and then a specific amount of water, just off the boil, is added. For example, for 12g (½ oz) of coffee, 200ml (7fl oz) of water might be added. The coffee is then left to steep for four minutes.

To end the brewing process, the layer of floating grounds on top of the bowl, called the crust, is stirred. This causes almost all of the coffee grounds to fall to the bottom of the bowl where they stop extracting. Any grounds and foam that remain on top can be skimmed off and the coffee is ready to taste.

Once the coffee has cooled to a safe temperature, tasting begins. Coffee tasters use a spoon to get a small sample of coffee, which they then aggressively slurp from the spoon. This slurping process aerates the coffee and sprays it across the palate. It is not essential to tasting, but does make tasting a little easier.

Before coffee reaches the consumer, professional tasters will grade and rank the coffee. Roasters and cafe owners will also taste the brew to check for flavour and quality control.

Before coffee reaches the consumer, professional tasters will grade and rank the coffee. Roasters and cafe owners will also taste the brew to check for flavour and quality control.

TASTING TRAITS

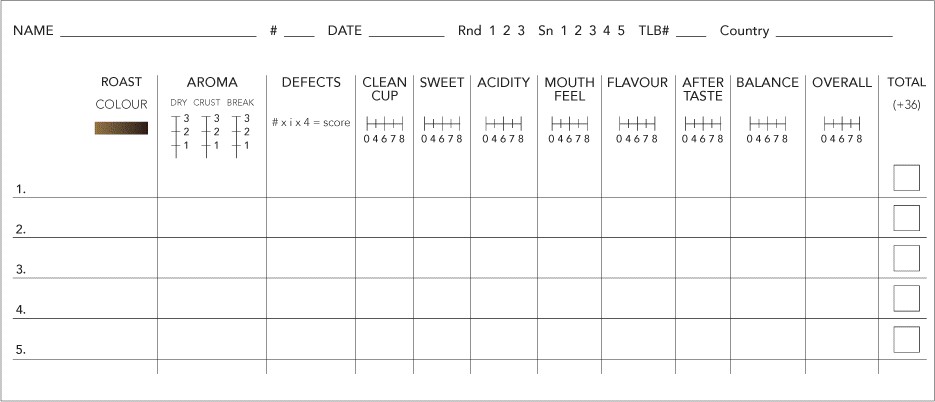

As coffee tasters work, they may record their notes on a score sheet. Different processes require different score sheets but in almost all cases the following attributes are being assessed:

SWEETNESS

How much sweetness does the coffee have? This is a very desirable trait in coffee, and generally the more the better.

ACIDITY

How acidic is the coffee? And how pleasant is this acidity? If there is a lot of unpleasant acidity, the coffee will be described as sour. A lot of pleasing acidity, however, gives the coffee a crispness or juiciness.

For many people learning to taste coffee, acidity is a difficult attribute. They may not have expected coffee to have much acidity, and certainly would not have considered this a positive quality in the past. Apples can be a great example of positive acidity: in an apple, high acidity can be wonderful, adding a refreshing quality.

Coffee professionals tend to develop a preference for high acidity in coffees, much as beer aficionados may develop a preference for very hoppy beers. This can result in a difference of opinion between industry and consumer. In the case of coffee, unusual flavours – such as fruit notes – are determined by the density of the coffee. Generally, denser coffees are also more acidic, so coffee tasters learn to associate high acidity with quality and interesting flavours.

MOUTHFEEL

Does the coffee have a light, delicate, tea-like mouthfeel or is it more of a rich, creamy, heavy cup? Again, more is not necessarily better. Low-quality coffees often have quite a heavy mouthfeel, coupled with low acidity, but are not always pleasant to drink.

BALANCE

This is one of the most difficult aspects of a coffee to assess. A myriad of tastes and flavours occur in a mouthful of great coffee but are they harmonious? Is it like a well-mixed piece of music, or is one element too loud? Does one aspect dominate the cup?

FLAVOUR

This is not just about describing the different flavours and aromas of a particular coffee, but also about how pleasant the taster finds them. Many new tasters find this the most frustrating aspect of coffee tasting. Each of the coffees they taste are clearly different but the language to describe them remains elusive.

A professional coffee taster will often use a score sheet similar to the one below to rate the different properties of a brew.

A professional coffee taster will often use a score sheet similar to the one below to rate the different properties of a brew.

HOW TO TASTE AT HOME

How does a professional coffee taster develop his skills so rapidly compared to a consumer? It isn’t through the use of cupping bowls or spoons. Neither is it by using score sheets, or having large amounts of data about where the coffee is from. It is through regular opportunities for comparative tasting. Where the coffee taster gains a quiet advantage is by going through a process of focused, conscious tasting and this can also be done at home very easily.

-

Buy two very different coffees. It is a good idea to ask your local coffee roaster or speciality shop for guidance. The comparative part of tasting is vitally important. If you taste just one coffee at a time you have nothing to compare it with and you are basing your judgements on your memories of previous coffees, which are likely to be patchy, flawed and inaccurate.

-

Buy two small French presses, as small as you can get, and brew two small cups of coffee. You could obviously do this with bigger presses and bigger cups, but this way will prevent excess waste or drinking too much coffee.

-

Let the coffee cool a little bit. It is much easier to discern flavours in warm rather than hot coffee.

-

Start to taste them alternately. Take a couple of sips of one coffee before moving on to the other. Start to think about how the coffees taste compared to each other. Without a point of reference, this is incredibly difficult.

-

Focus on textures first, thinking about the mouthfeel of the two coffees. Does one feel heavier than the other? Is one sweeter than the other? Does one have a cleaner acidity than the other? Don’t read the labels as you taste, instead note down some words about each coffee.

-

Don’t worry about flavours. Flavours are the most intimidating part of tasting, as well as the most frustrating. Roasters use flavours not only to describe particular notes – such as ‘nutty’ or ‘floral’ – but also to convey a wide range of sensations. For example, describing a coffee as having ‘ripe apple’ notes also communicates expectations of sweetness and acidity. If you do identify individual flavours, note them down. If not, then don’t worry. Any words or phrases that describe what you are tasting qualify as being useful, whether they are random words or specific flavours.

-

When you have finished, compare what you have written down with the roaster’s description on the packet. Can you see now what they are trying to communicate about the coffee? Often on reading the label your frustration will be relieved as you find the word to describe what you tasted. It can suddenly seem so obvious and this is part of building a coffee-specific vocabulary of flavours. Describing coffee gets easier and easier, though this is something even industry veterans still work on.

The skill of coffee tasting can be developed by comparative tasting. Choose and prepare a brew of two different coffees, then try comparing texture, taste, acidity and flavour.

The skill of coffee tasting can be developed by comparative tasting. Choose and prepare a brew of two different coffees, then try comparing texture, taste, acidity and flavour.