Roasting is one of the most fascinating aspects of the coffee industry. It takes the green coffee seed, which has almost no flavour beyond a quite unpleasant vegetal taste, and transforms it into an incredibly aromatic, astonishingly complex coffee bean. The smell of freshly roasted coffee is evocative, intoxicating and all-round delicious. This section deals with roasting on a commercial scale. See Home Roasting for information about home roasting.

A huge amount of research has gone into the commercial roasting of relatively low-quality coffee, most of it to do with the efficiency of the process and the methods used in producing instant soluble coffee. As these coffees aren’t particularly interesting or flavoursome, very little work has been done on the development of sweetness, or the retention of flavours unique to a particular coffee’s terroir or variety.

Speciality roasters around the world are, by and large, self trained and many have learned their trade through careful trial and error. Each roasting company has its own style and aesthetic, or roast philosophy. They may well understand how to replicate what they enjoy drinking, but they do not sufficiently understand the whole process to manipulate it to produce a variety of different roast styles. That is not to say that delicious and well-roasted coffee is rare: it can be found in almost every country in the world. If anything, it suggests that the future is bright for quality coffee roasting, as there is still a lot to explore and develop that can only lead to better roasting techniques.

FAST OR SLOW, LIGHT OR DARK?

To simplify matters, it can be said that the roast of a coffee is a product of the final colour of the coffee bean (light or dark), and the time it took to get to that colour (fast or slow). To simply describe a coffee as a light roast is not enough, as the roast could have been relatively fast or it could have been quite slow. The flavour will be quite different between the fast and the slow, even though the bean may look the same.

A whole host of different chemical reactions occur during roasting, and several of them reduce the weight of the coffee, not least of course the evaporation of moisture. Slow roasting (14–20 minutes) will result in a greater loss of weight (about 16–18 per cent) than faster roasting, which can be achieved in as little as ninety seconds. Slow roasting will also achieve a better, if more expensive cup of coffee.

The roasting process can be controlled to determine three key aspects of how the coffee will taste: acidity, sweetness and bitterness. It is generally agreed that the longer a coffee is roasted, the less acidity it will have in the end. Conversely, bitterness will slowly increase the longer a coffee is roasted, and will definitely increase the darker a coffee is roasted.

Sweetness is presented as a bell curve, peaking in between the highs of acidity and bitterness. A good roaster can manipulate where a coffee may be sweetest in relation to its roast degree, producing either a very sweet, yet also quite acidic coffee, or a very sweet, but more muted cup by using a different roast profile. However, adjusting a roast profile can never improve a poor-quality coffee.

The roasting process affects acidity, sweetness and bitterness of bean flavours. Roasters seek to balance these three aspects through carefully controlled use of heat and timing.

The roasting process affects acidity, sweetness and bitterness of bean flavours. Roasters seek to balance these three aspects through carefully controlled use of heat and timing.

THE STAGES OF ROASTING

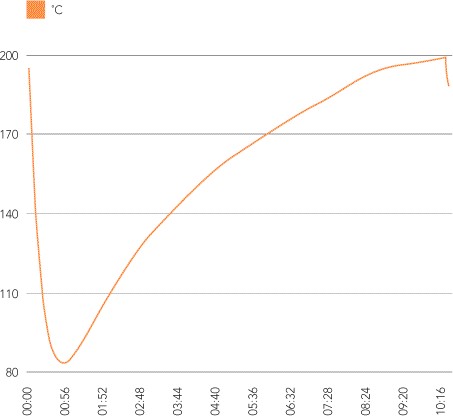

There are a number of key stages during roasting, and the speed at which a particular coffee passes through each of these stages is described as its roast profile. Many coffee roasters track their roast profiles carefully so they can replicate them to within very tight boundaries of temperature and time.

STAGE 1: DRYING

Raw coffee contains 7–11 per cent water by weight, spread evenly through the dense structure of the bean. Coffee won’t turn brown in the presence of water, and in fact this is true of browning reactions when cooking anything.

After the coffee is loaded into a roaster, it takes some time for the beans to absorb sufficient heat to start evaporating the water and the drying process therefore requires a large amount of heat and energy. The coffee barely changes in look or smell for these first few minutes of roasting.

STAGE 2: YELLOWING

Once the water has been driven out of the beans, the first browning reactions can begin. At this stage, the coffee beans are still very dense and have an aroma of basmati rice, and a little breadiness. Soon the beans start to expand and their thin papery skins, the chaff, flakes off. The chaff is separated from the roasting beans by the air flowing through the roaster and is collected and safely removed to prevent the risk of fire.

These first two roasting stages are very important: if the coffee is not properly dried then it will not roast evenly during the next stages and while the outside of each bean is well roasted the inside will essentially be undercooked. This coffee will taste unpleasant, with a combination of bitterness from the outside, and a sour and grassy flavour coming from the underdeveloped inside. Slowing the roasting process after this will not fix the problem as different parts of the coffee will always be progressing at different rates.

STAGE 3: FIRST CRACK

Once the browning reactions begin to gather speed there is a build-up of gases (mostly carbon dioxide) and water vapour inside the bean. Once the pressure gets too great, the bean will break open, making a popping noise and nearly doubling in volume. From this point onwards, the familiar coffee flavours develop, and the roaster can choose to end the roast at any point.

A roaster will see a decrease in the rate at which the coffee is increasing in temperature at this point, despite the fact that they may be adding a similar amount of heat. Failure to add enough heat can stall the roast and ‘bake’ the coffee, resulting in poor cup quality.

STAGE 4: ROAST DEVELOPMENT

After the first crack stage, the beans will be much smoother on the surface but not entirely so. This stage of the roast determines the end colour of the beans and the roast degree. Here the roaster can determine the balance of acidity and bitterness in the end product as the acids in the beans are rapidly degrading while the level of bitterness is increasing as the roast continues.

STAGE 5: SECOND CRACK

At this point the beans begin to crack again, but with a quieter and snappier sound. Once you reach second crack, the oils will be driven to the surface of the coffee bean. Much of the acidity will have been lost and a new kind of flavour is developing, often referred to as the generic ‘roast’ flavour. This flavour doesn’t depend on the kind of coffee used as it is a result of essentially charring or burning the coffee, rather than working with its intrinsic flavours.

Progressing a roast past the second crack usually results in the beans catching fire which is extremely dangerous, especially with large commercial roasting machines.

There are terms used in coffee roasting such as ‘French Roast’ or ‘Italian Roast’. Both of these terms are used to indicate very dark roasts, typically high in body and bitterness but with many of the characteristics of the raw coffees lost. While many enjoy coffees roasted in this manner, these kinds of roasts are not suitable for exploring the flavours and characteristics of high-quality coffees from different origins.

Coffee vendors have plied their aromatic trade for centuries, as depicted in this 18th-century engraving of a Parisian street hawker by Anne Claude Comte de Caylus.

Coffee vendors have plied their aromatic trade for centuries, as depicted in this 18th-century engraving of a Parisian street hawker by Anne Claude Comte de Caylus.

SUGARS IN COFFEE

Many people talk about sweetness when describing a coffee and it is important to understand what happens to the naturally occurring sugars during roasting.

Green coffee can contain reasonable quantities of simple sugars. Not all sugars are necessarily sweet to the taste, though simple sugars usually are. Sugars are quite reactive at roasting temperatures and, once the water has evaporated out of the bean, the sugars can begin to react to the heat in different ways. Some go through caramelization reactions, creating the caramel notes found in certain coffees. It should be noted, however, that the sugars that react this way become less sweet, and will eventually start to add bitterness. Other sugars react with the proteins in the coffee in what are known as Maillard reactions. This is an umbrella term covering the browning reactions seen in roasting a piece of meat in the oven, for example, but also when roasting cocoa or coffee.

By the time coffee has finished the first crack stage, there are few or no simple sugars left. They will all have been involved in various reactions resulting in a huge number of aromatic compounds.

ACIDS IN COFFEE

Green coffee contains many different types of acids, some of which are pleasant to taste and some that are not. Of particular importance to the roaster are the chlorogenic acids (CGAs). One of the key goals of roasting is to try to react these unpleasant acids away without creating negative flavours, or driving off the desirable aromatic components of the coffee. Some other acids are stable throughout the roasting process, such as quinic acid, which can add a pleasing, clean finish to a coffee.

AROMATIC COMPOUNDS IN COFFEE

Most of the aromatics in a good cup of coffee are created during roasting through one of three groups of processes: Maillard reactions, caramelization and Strecker degradation, another type of chemical reaction involving amino acids. These are all brought about by the heat during roasting and can result in the creation of over eight hundred different volatile aromatic compounds that flavour the cup of coffee. Although more aromatic compounds have been recorded in coffee than in wine, an individual coffee will only have a selection of these different volatiles. That said, the smell of freshly roasted coffee is so complex that all attempts to manufacture a realistic, synthetic version of this smell have failed.

ROAST PROFILE

Roasters track the temperature of the coffee beans during roasting: by changing how quickly a roast progresses at different times, the roaster can alter the flavour of the final coffee.

Roasters track the temperature of the coffee beans during roasting: by changing how quickly a roast progresses at different times, the roaster can alter the flavour of the final coffee.

QUENCHING

After roasting, the coffee must be cooled quickly to prevent over roasting or the development of negative (or ‘baked’) flavours. In small-batch roasting this is often achieved using a cooling tray, which rapidly draws air through the coffee to cool it down. With large batches of coffee, air alone is not effective enough: a mist of water is sprayed on to the coffee, and as it evaporates and turns to steam, it draws heat out of the beans. Done correctly, this has no negative effect on cup quality, but the coffee will age a little quicker. Unfortunately, however, many companies add more water than necessary to increase the weight of the beans and add monetary value to the batch. This is both unethical and bad for cup quality.

TYPES OF COFFEE ROASTERS

Coffee tends to be roasted close to where it will be consumed, as green coffee is more stable than roasted beans – coffee is at its best when used within a month of roasting. Roasting methods vary, but the two most commonly used types of machines are drum roasters and hot-air or fluid-bed roasters.

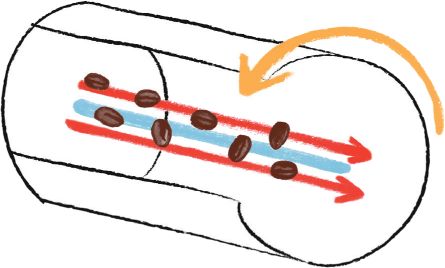

DRUM ROASTERS

Invented around the beginning of the 20th century, drum roasters are popular with craft roasters, as they are able to roast at slower speeds. A metal drum rotates above a flame, moving the coffee beans constantly during the process to aid even roasting.

The roaster can control the gas flame, and therefore the heat being applied to the drum, and can also control the flow of air through the drum, which dictates how quickly the heat is transferred to the coffee.

Drum roasters come in a range of different sizes, the largest being able to roast up to around 500kg (1,100lb) per batch.

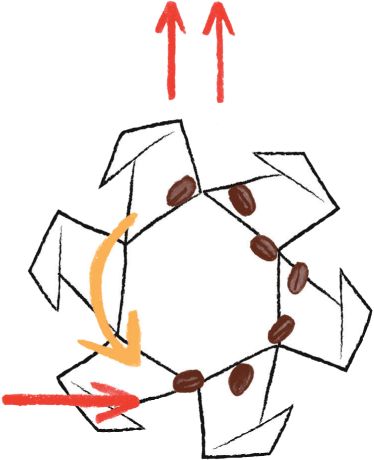

FLUID-BED ROASTERS

Invented by Michael Sivetz in the 1970s, fluid-bed roasters tumble and heat the beans by pumping jets of hot air through the machine. Roast times are significantly shorter than in a drum roaster so the beans tend to swell a little more as a result. The higher volume of air conducts heat more quickly into the coffee, which means that this roasting process is faster than drum roasting.

TANGENTIAL ROASTERS

Built by a company called Probat, tangential roasters are similar to large drum roasters but they have internal shovels to mix the coffee evenly during heating, which allows a bigger batch to be roasted effectively. The capacity isn’t much larger than a very large drum roaster, but this type is able to achieve faster roasting speeds.

CENTRIFUGAL ROASTERS

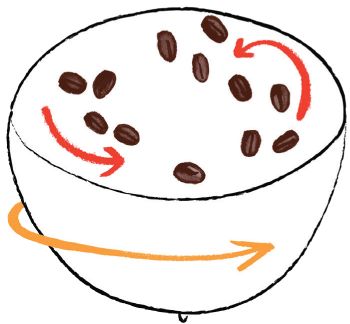

Centrifugal roasters allow very large quantities of coffee to be roasted incredibly quickly. The coffee is placed inside a large inverted cone, which spins to draw the coffee beans up the walls as they are heated. The beans are then flung back down into the middle of the cone to repeat their journey. Roast times can be as low ninety seconds using machines like this.

Roasting at very high speeds minimizes weight loss and increases the amount of coffee that can be extracted from the beans, which is important when making instant soluble coffee. Roasting at these speeds is not designed to produce the best possible cup.