It is often quoted that coffee is the second-most traded commodity in the world. It is not and, whether based on frequency or monetary value, is not even in the top five. Nonetheless, how coffee is traded has become a focus for ethical trade organizations. The relationship between the buyer and the producer is often seen as the First World exploiting the Third World. However, while there are undoubtedly those who wish to exploit the system, they are in the minority.

The price paid for coffee is generally quoted in US dollars per pound in weight ($/lb). There is something of a global price for coffee, often referred to as the C-price. This is the price for commodity coffee being traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Coffee production is often discussed in bags. A bag usually weighs 60kg (132lb) if it comes from Africa, Indonesia or Brazil, or 69kg (152lb) if it comes from Central America. While bags may be the units of purchase, on the macro scale coffee is usually traded by the shipping container, which contains around three hundred bags.

Contrary to popular belief, a rather small percentage of coffee is actually traded on the New York Stock Exchange, but the C-price does provide a sort of global minimum price for coffee, the minimum a producer would be willing to accept for his coffee. Prices for particular lots of coffee often have a differential added to the C-price, a kind of premium. Certain countries have, historically, been able to get higher differentials for their coffee, including Costa Rica and Colombia, although this type of trading is still mostly focused on commodity grade, rather than speciality coffee.

The problem with basing everything on the C-price is that this price is somewhat fluid. Usually prices are determined by supply and demand, and to some extent this is true of the C-price. As global demand increased at the end of the 2000s, the market saw an increase in price and coffee supply began to look scarce. This produced one of the highest spikes in the price of coffee, reaching above $3.00/lb in 2010.

This price wasn’t simply about supply and demand, however, it was also influenced by other factors, not least the influx of cash into the industry from traders and hedge funds who saw an opportunity to make money. This produced a volatile market, the like of which had never really been seen before. From that spike, prices steadily declined again to levels that can be considered unsustainable for profit.

Coffee bags being loaded on to ships at the port of Santos, Brazil, in 1937. Nowadays coffee is usually transported in shipping containers, which hold around three hundred bags each.

Coffee bags being loaded on to ships at the port of Santos, Brazil, in 1937. Nowadays coffee is usually transported in shipping containers, which hold around three hundred bags each.

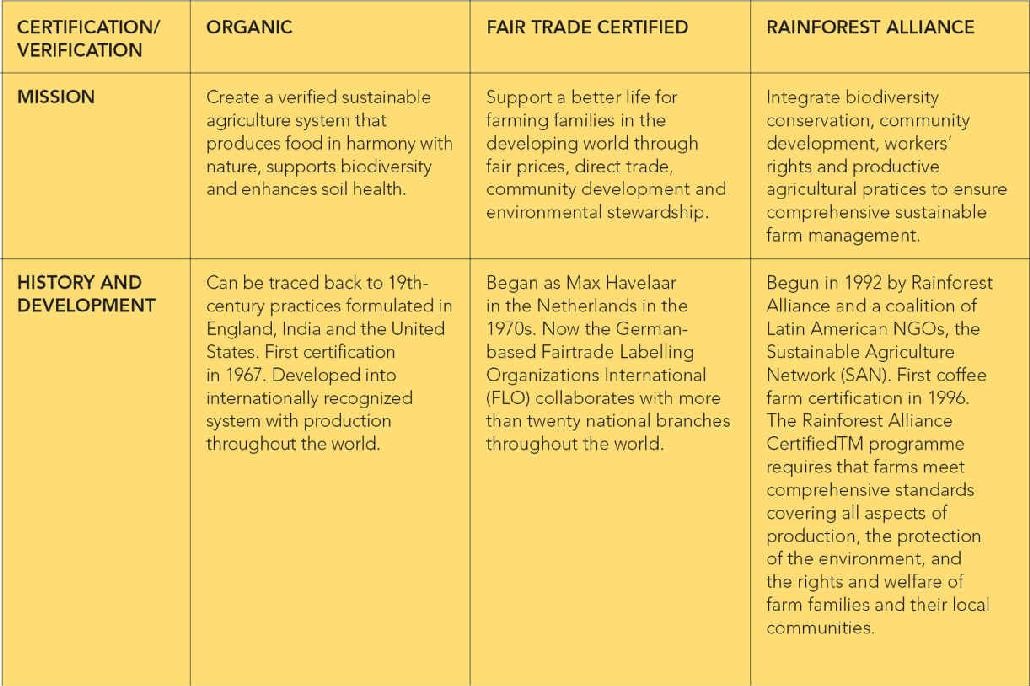

The C-price for coffee does not reflect the cost of production, and as such producers may end up in a position where they lose money growing coffee. There have been a number of reactions to this problem and the most successful has been the Fair Trade movement, although there are many other sustainable coffee certification schemes, including those of the Organic Trade Association and the Rainforest Alliance (see box).

FAIR TRADE

There remains some confusion about exactly how Fair Trade works, although it has undoubtedly become a successful tool to help those who wish to purchase coffee with a clear conscience. Many people presume that the promises of Fair Trade are far wider reaching than they actually are, and that any coffee could (in theory) be certified as Fair Trade. This is not the case. And to make matters worse, it is easy for detractors to allege that the farmer is not getting the premium because of the complex nature of financial transactions within the coffee industry.

Fair Trade guarantees to pay a base price that it considers sustainable, or a $0.05/lb premium above the C-price if the market rises above Fair Trade’s base price. Fair Trade’s model is designed only to work with cooperatives of coffee growers, and as such cannot certify single estates that produce coffee. Critics complain about a lack of traceability or true guarantee that the money definitely goes to the producers, and isn’t diverted through corruption. Others criticize the model for providing no incentive to farmers to increase the quality of their coffee. This has encouraged many in the speciality coffee industry to change the way they source their coffee, moving away from the commodity model, where coffee is bought at a price determined by global supply and demand and little regard is given to its provenance or quality.

THE SPECIALITY COFFEE INDUSTRY

A number of different terms are used to describe the various ways in which speciality roasters are buying their coffee and their relationships with the growers.

Relationship Coffee is used to describe an ongoing relationship between producer and roaster. There is usually a dialogue and collaboration to work towards better quality coffee and more sustainable pricing. For this arrangement to have the desired positive impact, the roaster would have to be buying the coffee in sufficient quantity.

Direct Trade is a term that has arisen more recently, where roasters wish to communicate that they bought the coffee directly from the producer, rather than from an importer, an exporter or another third party. The problem with this message is that it plays down the important role of importers and exporters in the coffee industry, potentially unfairly portraying them as middlemen simply taking a slice of the producer’s earnings. To be viable, this model also requires the roaster to buy enough coffee to make an impact.

Fairly Traded may refer to a purchase where there has been good transparency and traceability and high prices have been paid. There is no certification to validate the ethics of the purchase, but those involved are generally trying to do good with their trading. Third parties may be involved but are considered to have added value. This isn’t a very commonly used term, except in situations where a customer asks if a particular coffee is Fair Trade.

The idea behind all these buying models is for roasters to try to buy more traceably, to remove unnecessary middlemen from the supply chain, and to pay prices that incentivize the production of higher quality coffee. However, these terms and ideas are not without their critics. Without third-party certification it can be difficult to ascertain whether or not a roaster is actually buying the way they say they are. Some roasters may buy coffees that have been kept traceable by importers and brokers, and claim this as a direct trade or relationship coffee.

There are no guarantees of a long-term relationship for the producers either, with some coffee buyers simply chasing the best lots of coffee they can each year. However, at least they are paying handsomely for it. This type of approach makes long-term investment in quality difficult and it should also be noted that some middlemen provide a valuable service, especially to those who are working on a smaller scale. The logistics of moving coffee around the world require a level of specialization and skill that many small roasters simply do not have.

ADVICE TO CONSUMERS

When buying coffee, it is difficult for consumers to ascertain how ethically sourced a particular coffee really is. Some speciality roasters have now developed buying programmes certified by third parties, but most have not. It is fairly safe to presume that if the coffee has been kept traceable, has the producer’s name(s) on it, or at least the name of the farm, cooperative or factory, then a better price has been paid. The level of transparency you should expect will vary country by country, and is covered in more detail in each of the sections on the producing countries. If you find a roaster whose coffee you like, you should be able to ask them for more information about how they source it. Most are more than happy to share this information, and are often extremely proud of the work they do.

AUCTION COFFEES

There has been a slow and steady increase in coffees that are sold through internet auction. The typical format for this involves holding a competition in a producing country wherein farmers can submit small lots of their best coffee. These are graded and ranked by juries of coffee tasters, usually a local jury for the first round and then an international cadre of coffee buyers will fly in for the final round of tasting. The very best coffees are sold at auction and generally achieve very high prices, especially the winning lot. Most auctions display the price paid for the coffee online, allowing full traceability behind the whole process.

This idea has also been embraced by a small number of coffee-producing estates that have managed to build up a brand based on the quality of their coffee. Once they have sufficient interest from international buyers they can make an auction work. This idea was pioneered by a farm in Panama called Hacienda La Esmeralda, a farm that had previously set records for the huge prices paid for its competition-winning coffees.

Harvested coffee cherries are sorted and cleaned to remove unripe and overripe fruit as well as leaves, soil and twigs. This is often done by hand, using a sieve to winnow away unwanted materials.

Harvested coffee cherries are sorted and cleaned to remove unripe and overripe fruit as well as leaves, soil and twigs. This is often done by hand, using a sieve to winnow away unwanted materials.